The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has asked for comment on a new direct provider contracting model. We are pleased to see CMS’s continued interest in exploring new avenues of value driven health care and grateful for the opportunity to participate in the development process.

Aledade and its partner practices participate in shared savings arrangements through the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and partnerships with commercial payers, Medicare Advantage plans, and Medicaid. We also have experience with other CMMI models, including CPC+, and models based on PCMH and/or quality metrics sponsored by commercial and Medicare Advantage plans.

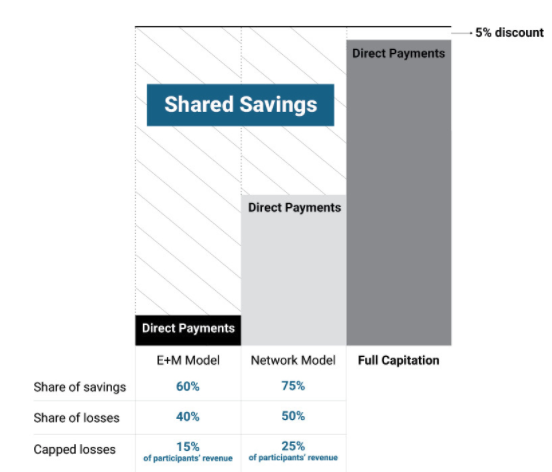

With the continued introduction of competing, and sometimes overlapping value-driven models, the final question of the RFI (#21) is particularly relevant. Is there a need for another value-based model? Yes, we believe that the need is clear. Nearly every model today is based on a fee-for-service (FFS) chassis and a standard benefit design. Today, our practices are divided between FFS-supported activities and activities that must generate shared savings to have a return. A new DPC model could create a new pathway for additional investments in population health by allowing for the redirection of current FFS revenue towards value. We recommend that the new DPC model offer three levels of conversion of FFS revenue into direct payments, each combined with increasing levels of accountability for total cost of care and quality.

Both CPC+ Track 2 and Next Generation ACO experiment with some level of direct payments; however, CPC+’s accountability for total cost of care and quality is too weak and Next Generation ACO requires a level of risk taking that is excessive for many physician practices. The DPC Model could address these challenges by testing a direct payment that replaces fee schedule driven for certain services combined with accountability for total cost of care that scales between the tiers selected by the model participants.

Tier 1: E&M

This tier would replace E&M billing by the primary care physicians in the model with risk adjusted direct payments. Combined with a shared savings model based on total cost of care, this tier of the DPC model would allow participating physicians to best direct their time and efforts toward the health of their patients. Under this model, physicians would receive a 10% increase in total primary care payments compared to historic averages, and have the flexibility in how they deliver primary care services in return for assuming accountability for the total cost of care. Physicians would share in 60 percent of the resulting savings and be accountable for up to 15 percent (5% net) of their total Medicare payments if total cost of care exceeds benchmarks.

Tier 2: Network

This tier allows the participating physicians to create a network for DPC larger than the primary care providers that participate directly in the model and more inclusive of services beyond the Tier 1 E&M services. This tier has the greatest similarity to an existing model, the affiliate program in Next Generation ACO. However, we recommend both lower financial reward and accountability than in Next Generation ACO. The model participants would share in 75 percent of the savings and risk 25 percent of their total Medicare payments.

Tier 3: Full Capitation

This tier allows for full accountability for the total cost of care within traditional Medicare as a true alternative to Medicare Advantage. Model participants would have full access to the total cost of care payments not as a shared savings reconciliation, but a prospective payment into a virtual account to which both CMS (to pay claims) and the model participants (to fund services) have access. Model participants would provide all of the traditional Medicare benefits either directly or from other health care providers who would bill Medicare through the terms of their network contract with the model participants — or, if such a contract does not exist, based on traditional Medicare fee for service. Medicare would pay for those services from the account of the model participants. We propose to benefit the Medicare trust fund by reducing the direct payment rates for total cost of care by five percent.

Benchmarking Total Cost of Care

No model can survive an unpredictable benchmark. Unexpected losses result in model dropout and, if done poorly, possibly provider bankruptcy. Even uncertainty in benchmarks that do not result in losses erode confidence in the program. Yet an outcome-based program will always have more uncertainty than fee for service. A successful benchmark must strike the right balance. We have three principles for this balance:

- Benchmarking should transition from a historical to market basis on a known timeline.

- CMS should utilize existing policies wherever possible for simplicity.

- Downside risk should not be ruinous for the model’s participating providers.

The total cost of care benchmark should mimic the Medicare Shared Savings Program benchmark methodology (with corrections for existing problems with regional benchmarking and risk adjustment as explained in another recent publication in the American Journal of Managed Care). Not only does this create simplicity in benchmarking, but it makes choosing between DPC and MSSP more straightforward for participants. We also propose to align historic and regional benchmarks with Medicare Advantage premiums as explained in greater detail in this New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst article.

We propose to use MA benchmarks because they are well established, and they already address many of the challenges faced by new models:

- Benchmarks are set on a traditional FFS basis.

- Low-cost areas are rewarded and high-cost areas are penalized.

- Quality is financially accounted for.

- Risk adjustment is incorporated and adjusted for.

We find the simplicity of adopting MA rates to outweigh any real and/or perceived concerns (we have a few ourselves) with the calculation of the MA benchmarks. Any changes to MA benchmarking methodology over time should carry through to the model as well. We offer these additional principles for creating the Tier 3 benchmark.

- In full capitation the transition to a regional basis should be much faster (possibly immediate) than in a shared savings model

- Risk adjustment is critical to separate insurance risk from provider performance on value

- The benchmark should be prospective with only limited reconciliation as it is in MA

We believe this new DPC model can open the door to much greater transformation than any other model currently offered by CMS. Coupling direct payments with accountability for total costs provides an opportunity to move away from the limitations of FFS. And a tiered framework promotes participation for a wide variety of practices, including small, independent practices such as those in Aledade Accountable Care Organizations.

Addressing Benefit Design

The model outlined above moves away from the fee-for-service chassis, but does not move away from the traditional Medicare benefit design. Consideration of benefit design is coupled with consideration of whether beneficiaries should be attributed to a model or whether they must choose to enroll in the model. We see a very clear line on when enrollment is necessary.

Anytime a beneficiary is subject to a restriction in providers or a less generous benefit than in traditional Medicare, the beneficiary should choose to enroll in the model.

In fact, we think the statute may require such a structure. Section 1115A allows the Secretary to . expand a model only if he or she “determines that such expansion would not deny or limit the coverage or provision of benefits under the applicable title for applicable individuals.” Models that do not restrict providers and only offer the same or more generous benefits than traditional Medicare can rely on data-driven attribution to the model.

We believe there could be a place for both types of benefit design in each tier of the DPC model. We take it as self-evident that an attribution-based model will have much greater participation than an enrollment-based model. At the same time it is entirely possible that an enrollment-based model that allows for a narrow network and/or higher copays — say, on low-value services and drugs — could generate significant additional savings over an attribution model that cannot alter the benefit design to the same degree.

We recommend that CMS offers both options to model participants in all tiers.

- Attribution Based Model: Model participants can use waivers to offer more generous benefits to all or specific Medicare beneficiaries than are available in traditional Medicare.

- Enrollment Based Model: Model participants must enroll Medicare beneficiaries, but receive much more comprehensive waivers on benefit design, more analogous to what is available in MA, specifically VBID.

We believe there is significant opportunity for a DPC model that tests moving off of the FFS chassis and off the traditional Medicare benefit design. We further believe that by offering different degrees of movement away from both the FFS chassis and traditional benefit design the model can attract a wide variety of practices, including small, independent practices. We would strongly oppose limiting DPC models to a purely enrollment-based approach, as that would discourage participation and limit the scale of the model and the benefits to Medicare beneficiaries while imposing additional administrative burdens on practices that do not wish to engage in the benefit design opportunities of an opt-in model.

The advantages of coupling accountability for total cost of care with opportunities for health care providers to better spend revenue currently tied up in FFS is a true example of 1 + 1 = 3. Not only does accountability for total cost of care given health care providers focus on the entirety of the patient experience and offer greater incentivizes for success, it avoids many of the pitfalls of direct payment by accomplishing on an outcome basis what would be impossible to accomplish through a compliance monitoring process. We look forward to continuing to work with CMS and all payers on creating the most value for a health care dollar.