By Travis Broome and Farzad Mostashari

Last week, we outlined how the ACO model and the Medicare Shared Savings Program in particular are prepared for COVID-19 and make our response stronger. In this follow up we dive into the design of MSSP to understand how it will cope with COVID-19.

At a time when many primary care practices are facing a severe reduction in fee-for-service income due to the COVID-19 outbreak, it is good to consider what the impact of the outbreak might be on the revenue of the 30% or more primary care practices that have entered alternative payment models through the Medicare Shared Savings Program. To put the bottom line upfront- the design of the Pathways to Success program protects these practices from most cost increases due to the outbreak, although CMS should take action within their authority to shield these practices from the disruption caused by the outbreak in collecting and reporting quality measures.

The Fundamentals of How MSSP Determines ACO Savings

An ACO’s job is to outperform cost expectations while improving the quality of care. At the beginning of every MSSP contract, an ACO is assigned a benchmark that sets those cost expectations. The benchmark is the basis for all of the financial performance of the ACO for the next five years. Every year the benchmark is trended forward based on regional and national changes in Medicare costs from the previous year. The amount of national benchmark applied is in direct proportion to the market share of an ACO in their region.

The main savings driver for an ACO is performing better than these regional and national cost trends. It does not matter to an ACO if the trend is twelve percent or three percent, what matters is whether the ACO can do better. If an ACO’s costs go up four percent when the trend is twelve percent the ACO generates eight percent savings. If the ACO’s costs go up four percent when the trend is three percent the ACO generates one percent losses. In MSSP, all of the trends are based on actual experience. CMS does not attempt to guess how costs will change in 2020 before the year has started. Instead, they simply measure the true expenditures at the end of the year. This is an important distinction from other programs, such as Medicare Advantage, where trend is projected ahead of the start of 2020. Those projections do not account for unexpected changes in costs due to events like COVID-19, while the design of the MSSP model accounts for any widespread cost trends by simply folding them into the final benchmark calculation.

We currently do not have a good estimate for what the cost impact of COVID-19 will be on insurers and risk-taking providers. Certainly, the health care system will be spending enormous resources to combat the pandemic. We do not know how much of that cost will be reimbursed through the health insurance system or through emergency funding. We do not know how much those costs will be offset by postponed or canceled specialist visits, elective procedures, and surgeries. How, when, and if those services are eventually delivered will determine the balance of payments. Whatever the balance ends up being, it will be expressed in the cost trend. The ACO’s job remains the same: combine excellence in population health and excellence in primary care to do better than trend; to exceed expectations.

A COVID-19 Hypothetical

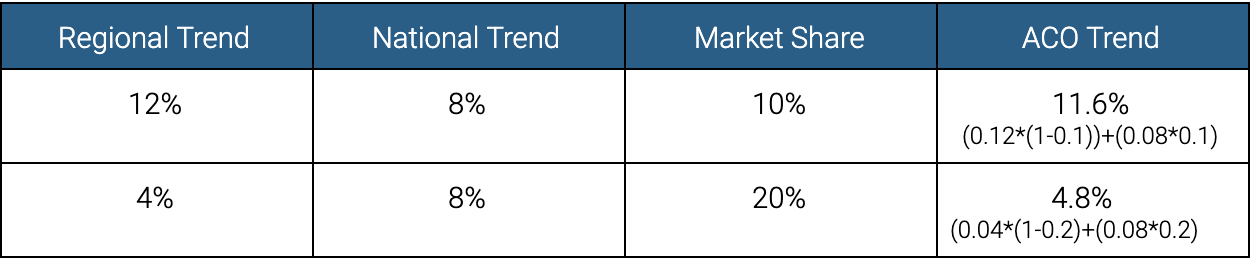

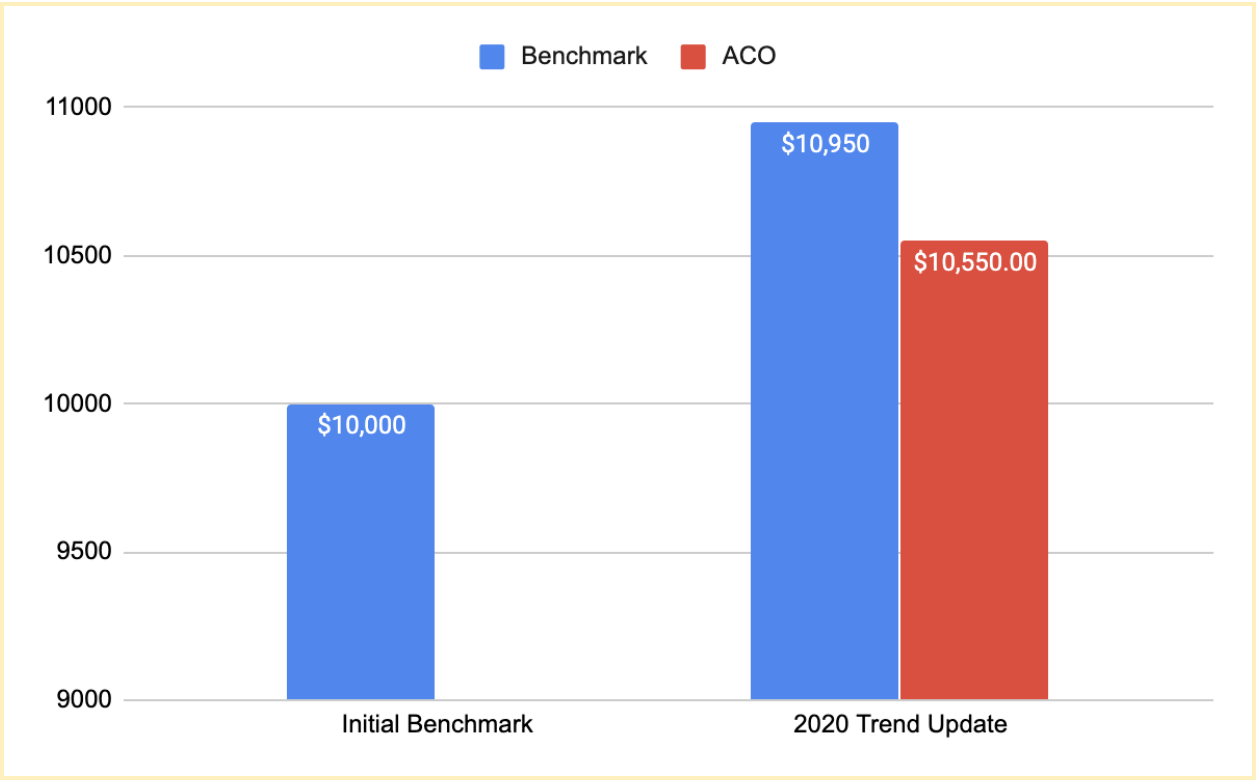

Let’s walk through a hypothetical 2020 benchmark update. Our example ACO had an initial benchmark of $10,000. At the end of 2020 that benchmark will be updated by our three factors. Let’s assume first that the region our ACO is in gets hit harder than the nation as a whole, so we will assign twelve percent to our regional trend and 8% to the national trend. To know how much regional trend to use and how much national trend to use we need to know how many of the region’s Medicare beneficiaries are assigned to our ACO. Our example ACO has a ten percent market share. Therefore, the regional trend makes up ninety percent of the ACO trend and the national trend makes up the remaining ten percent of the ACO trend. The ACO trend is 11.6%, and the impact on the ACO is only -0.4% of lost savings.

On the other hand, let’s assume an ACO in a rural area that gets hit less hard than the nation as a whole (and in which we are a larger share of the total market). In this example, ACO has a twenty percent market share. Therefore, the regional trend makes up eighty percent of the ACO trend and the national trend makes up the remaining twenty percent of the ACO trend. The ACO cost trend would be 4.8%, and the impact on the ACO would be +0.8% in savings.

An ACO can generate savings even if its final costs are considerably higher than its initial benchmark as long as it outperforms cost trends.

With the actual trend as a result of COVID-19 in place, an ACO in MSSP is mostly measured on how it performed during COVID-19, not on what the world would have been absent COVID-19.

Two Reasons CMS Should Stay Vigilant

First, the measurement of quality will be very different in 2020. Second, there are certainly reasons an ACO may differ from its regional trend negatively that are beyond its control.

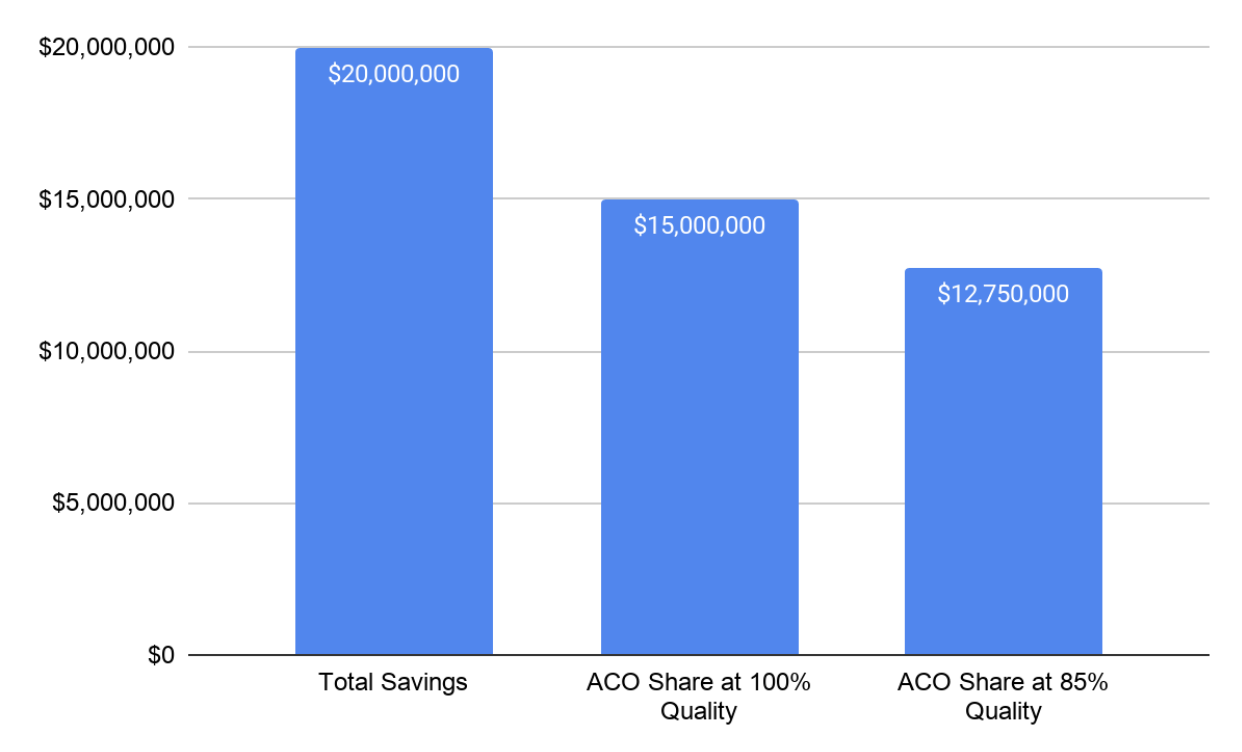

When an ACO generates savings, its quality score determines how much of those savings it earns. Many of the measures are preventative screening measures. Care that normally covers those measures is currently being postponed across the country. We have no idea how big the backlog will be once we resume normal care. All of the quality measure benchmarks were set prior to the pandemic. Every percent reduction in an ACO’s risk score results in a percent reduction in earned shared savings payments. If our example ACO generated $20,000,000 in savings and was in the Enhanced track at 100% quality they would receive $15,000,000; at 85% quality they would receive $2,250,000 less.

CMS’s mechanism to control for disruptions due to public health emergencies is to assign national average quality to the ACO. This is problematic during the current pandemic in two ways. First, high performing ACOs have higher than average quality and may prefer their actual scores. Second, the national average quality may fall during the pandemic shifting savings from health care providers to Medicare at a time when health care providers are already strained financially. A better solution would be to carry over ACO’s quality scores from the previous year. ACOs in their first year are paid for reporting so every ACO scored on performance has a prior year performance to use.

Conclusion

The MSSP is the best model design we have to deal with a pandemic like COVID-19. Yet COVID-19 has no modern parallel. CMS must stay vigilant as the year progresses to ensure that during this national emergency individual ACOs are protected against things beyond their control. Now is not the time for assuming “it averages out”. As a community, ACOs are responding to the outbreak in amazing ways. The best of the responses will even generate more savings than normal.

Today, the design of MSSP allows us all to focus on the needs of our communities even as we retain accountability for the cost and quality of care received by our patients. Now, more than ever, it is clear that primary care doctors would be wise to diversify their practice revenue by adding a value-based payment stream on top of the fee-for-service reimbursement that currently provides the foundation of funding for their practices.